I recently finished a book written 20 years ago about McDonalds that chronicled the history, successes and struggles from the 1950's through 1986. Included were a few stories of how McDonalds suffered when they mishandled certain public relation issues and how they learned from those mistakes to become a stronger company.

Now with Social Media creating fast growing networks of communication via the internet, how an established brand acts and reacts can spread instantly.

Take a look at this article from EConsultancy.com:

Social media has given brands a new medium in which consumers can be engaged. Most agree: there's something really important about this, even if we disagree on just what that is.

Social media has given brands a new medium in which consumers can be engaged. Most agree: there's something really important about this, even if we disagree on just what that is.

At the same time, social media has given consumers a powerful new tool for interacting with brands. It's now possible to provide feedback, issue praise and voice complaints in a manner that can have a real impact very quickly.

But what if some brands are paying too much attention to social media? Is it possible that the most vocal on Facebook and Twitter and in the blogosphere not only don't represent the majority of consumers but might also be providing signals that go against what the majority believes?

AdAge.com has an interesting article that raises these very questions and offers up some hard data to demonstrate why brands should be asking them.

You may recall the uproar that occurred in the social media world when a Motrin ad discussing the pitfalls of carrying a baby in a sling and referring to the act as a fashion statement were discovered by some 'mommy bloggers'. The uproar reached a fever pitch on Twitter and Motrin, which is a Johnson & Johnson brand, relented. It pulled the ad and issued an apology.

Gene Grabowsk, who heads up the crisis and litigation practice at Levick Strategic Communications, stated at the time:

We now have indisputable proof that online marketing, YouTube and Twitter and all that it encompasses is meaningful and has arrived.

Forrester's Jeremiah Owyang commented:

These tools allow advertisers to listen to what people are saying — and can provide free, instant feedback before they buy marketing efforts in traditional media.

But there's a problem, which Ad Age's Abbey Klaassen points out in her article: according to a survey conducted by Lightspeed Research, 90% of the women surveyed had never even seen the ad. After seeing it, 45% liked it, only 15% didn't like it. More importantly, 32% said the ad make them like the Motrin more compared to only 8% who thought less of Motrin after seeing it.

With actual data in hand, it's much more difficult to conclude whether or not Motrin made the right decision in pulling the ad. It had an ad that was relatively effective according to the survey data, but the qualitative response from a small but vocal group of moms was so poor that it's easy to see why Motrin made the decision that it did.

Motrin is not an isolated example.

Remember the Skittles Twitter experiment we wrote about here at Econsultancy? It created a lot of buzz amongst social media folks but according to a Communispace survey of 300 people, only 6% had ever heard that Skittles' turned its site into a Twitter feed. Interestingly, 64% of the Communispace audience surveyed had heard of Twitter but few were users and over 50% had learned about Twitter on TV.

Both Motrin and Skittles raise the question: are brands listening to the right people when they hone in on what people are saying on social media sites?

Depending on who you are and what you sell, the answer just might be an emphatic 'no'!

Klaassen observes:

...in the past month, the Twitter community has been titillated by South by Southwest, AT&T, "Lost" and the redesign of Skittles.com. Missing from the list are things the Communispace and Lightspeed surveys, both separately commissioned on Ad Age's behalf, found that the general population is fired up about, such as the AIG bonuses and the bank-bailout plans.

So what are brands to do? They're going to have to be more thoughtful, discriminating and strategic for starters. Social media shouldn't be ignored but at the same time it shouldn't be given more weight than it deserves.

If brands are going to use social media services to solicit feedback and make important decisions, they can't just take a qualitative approach. Hard data is needed. Just as focus groups are carefully selected and surveys are discounted if the sample size and sample makeup isn't representative, what people are saying about you on Facebook or Twitter can't be overestimated in the absence of quantitative data showing that what they're saying is representative of consumers at large.

By all means, listen. But think before acting. You can't please all of the people all of the time and most brands have always recognized that when it comes to traditional media channels.

For some reason, social media has them thinking differently. I think part of it has to do with the fact that traditional mediums aren't working quite like they used to and brands are worried. There is a media revolution taking place, consumers are feeling empowered and social media is important.

But far too many of us in the digital marketing community have spent the past years admonishing brands and basically telling them that they're stupid. We keep telling them that the consumer is in control, that they have to participate in social media and that if they don't listen to what people on Facebook, Twitter and blogs are saying, they'll find themselves in reputation hell.

And by golly, many of them have started to believe us. They're willing to pull ads when a handful of bloggers with a few thousand readers complain. They'll turn their homepages over to Twitter. They'll do a lot of things to avoid being labeled as 'not getting it'.

After reading AdAge.com's article, I'm finally ready to admit publicly that I'm not so sure I like it. We have brands far too scared.

If our job as digital marketers is really to help brands connect with consumers to produce meaningful interactions, relationships and yes, transactions, we can't have them acting out of fear. We shouldn't be telling them to listen to anybody with a blog. We shouldn't be telling them to use Twitter simply because we think they need to be on it. We shouldn't tell them that consumers on Facebook are more important than consumers who aren't 'connected'.

We should be telling them to apply common sense to decision-making and we should be telling them to implement social media strategies that are based on hard data and validated business cases. And as much as I love sites like Twitter and Facebook, if that means telling brands to ignore social media uprisings that threaten to create a 'tyranny of the few' dynamic when it comes to brand decision-making, so be it.

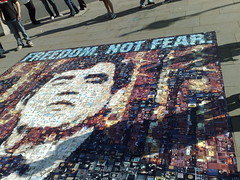

Photo credit: jamescronin via Flickr.

Patricio Robles is a tech reporter at Econsultancy. Follow him on Twitter. Sphere: Related Content

No comments:

Post a Comment